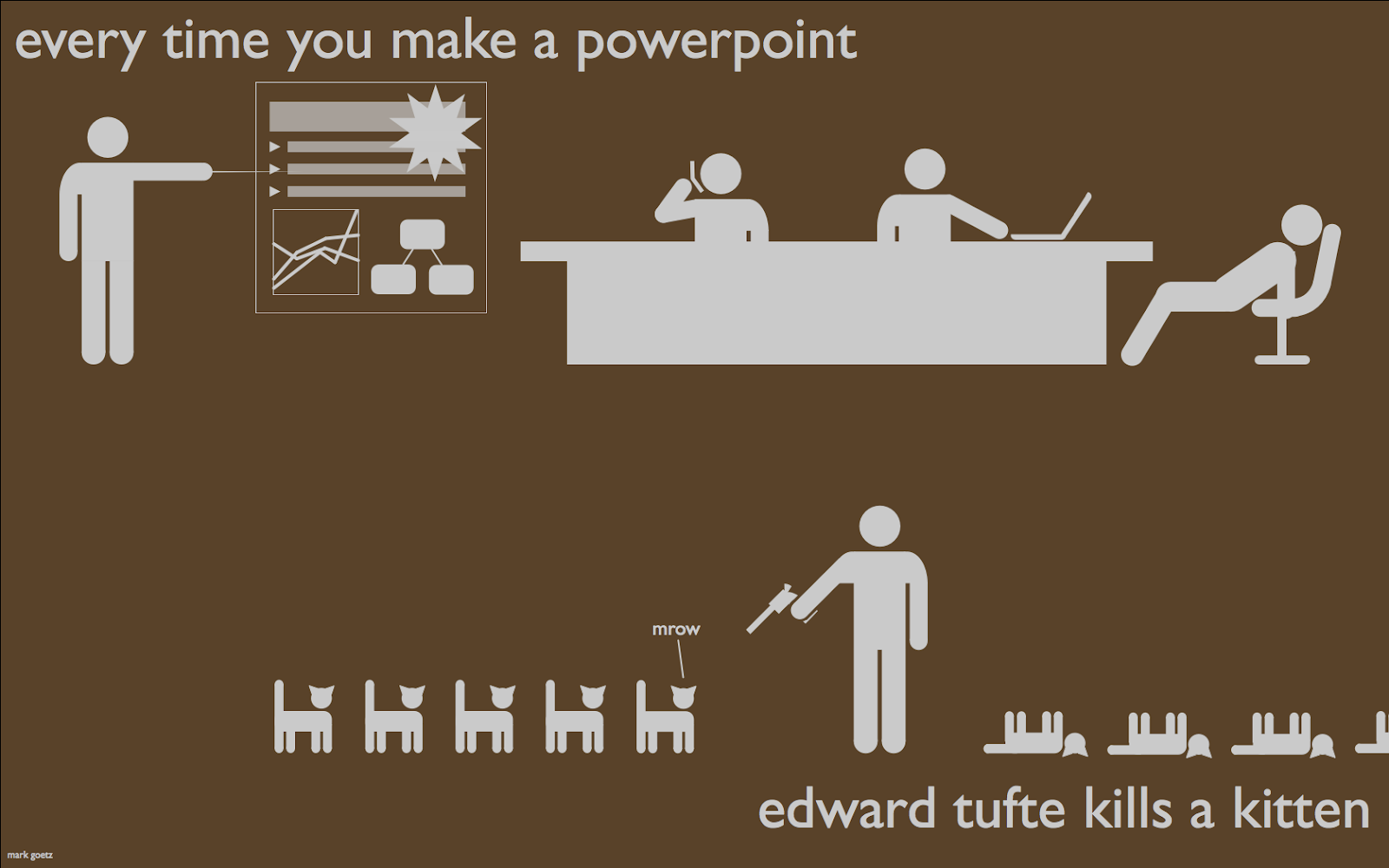

Many people have very strong - mostly negative - opinions about PowerPoint. The phrase "death by PowerPoint" has been used (maybe over-used) to describe the painful experience of sitting through a bad PowerPoint presentation. Let's begin with some thoughts from Edward R. Tufte - professor emeritus of political science, computer science and statistics, and graphic design at Yale. In a September 2003 Wired Magazine article

PowerPoint is Evil Tufte illustrates his thesis with a really creative metaphor:

Imagine a widely used and expensive prescription drug that promised to make us beautiful but didn't. Instead the drug had frequent, serious side effects: It induced stupidity, turned everyone into bores, wasted time, and degraded the quality and credibility of communication. These side effects would rightly lead to a worldwide product recall.

Slideware may help speakers outline their talks, but convenience for the speaker can be punishing to both content and audience. The standard PowerPoint presentation elevates format over content, betraying an attitude of commercialism that turns everything into a sales pitch.

One could sum up the sentiment by borrowing and adapting a phrase from Security Consultant and blogger

Steve Riley - PowerPoint is "... the place where knowledge goes to die."

While we don't disagree with Tufte and other critics that the use of PowerPoint is part of an ever-present misconception that technology fixes things or makes things better, we're not here to pile on--instead we'd like to offer some ideas to make PowerPoint more effective in your classroom. While technology can and has provided some great benefits to society, it's not a panacea - you can't just throw PowerPoint into the classroom and turn a poor lecturer into a good lecturer or a good lecturer into a great lecturer. Tufte gets it right when he says:

Presentations largely stand or fall on the quality, relevance, and integrity of the content. If your numbers are boring, then you've got the wrong numbers. If your words or images are not on point, making them dance in color won't make them relevant. Audience boredom is usually a content failure, not a decoration failure.

So how do we become better presenters? Most teachers would agree that there's no better way to learn how to do something than by watching and learning from people who are great at what they do, so we'd like to share with you today some interesting and innovative presentations that hopefully will inspire you to look at PowerPoint and technology in new and different ways. The first is the 2005 Open Source Convention keynote--Identity 2.0--from Sxip Identity founder and CEO Dick Hardt.

What's interesting and unique about this presentation is the style. In a presentation that lasts only 15 minutes, Hardt uses hundreds of slides--many with just a single word or image--to tell a story that is rapid-fire, humorous and engaging.

At the end of the presentation, Hardt credits

Lawrence Lessig - Director of the

Edmond J. Safra Foundation Center for Ethics at

Harvard University, and a Professor of Law at

Harvard Law School--for inspiring his presentation style. That said, here is example number two--Lawrence Lessig's presentation from the 2007 TED (Technology, Entertainment, Design) Conference. This is a shortened (20-minute) version of Lessig's Free Culture presentation.

What we can learn from Lessig (considered the master of the simple slide show) and Hardt is to break free from the constraints of PowerPoint--the titles and the bullet lists and the charts. Also consider how Lessig expertly weaves together humor, video, and storytelling to create his narrative and ultimately make his case.

The final example is Guy Kawasaki's

Art of the Start speech at TiECon 2006 - the annual meeting of The Indus Entrepreneur organization. Kawasaki gives a great presentation about innovation and business evangelism, speaking plainly and peppering the presentation with humor.

Some of the key points Kawasaki makes are:

- abandon the traditional business paradigm of Mission Statements in favor of shorter, more meaningful 3-4 word Mantras; and

- adopt the 10/20/30 rule for presentations--no more than 10 content slides (Kawasaki favors top ten lists); no longer than 20 minutes (his presentation is nearly 40-minutes); and use nothing smaller than a 30 point font.

We really like the Mission versus Mantra discussion--it really parallels the Lessig/Hardt approach of simple is better. The 10/20/30 rule is interesting as well. While it may not work or be right for everyone, it does accomplish a few things--the 10 gets you and your audience to focus on 10 key points you'd like to get across (Mike uses takeaways); the 20 keeps the presentation short and digestible; and the 30 ensures that you HAVE to know what you're talking about--you can't read it off the slide, because it's not there.

We encourage you to watch and re-watch these videos and to try out some of what you see. Take one of your lectures and try the 10/20/30 rule or "simplify" it like Lesig and Hardt or come up with your own unique style. The key is to focus on the content and the learning and not get seduced by the technology, the animations, or the bullet lists. So, open up your mind, set aside your preconceptions; don't view PowerPoint as a crutch or as a substitute for your lecture, but instead as a spark that can ignite and excite an audience. And lastly, don't ignore Tufte's most important rule of speaking:

Respect your audience.